There’s a kind of reading that doesn’t show up in metrics. It doesn’t leave highlights or annotations. It’s quiet, interior. A sentence snags in the mind. A half-formed picture flickers behind the eyes. You pause not because the app told you to, but because something in the language made the world feel briefly strange. Or familiar.

This kind of reading is still possible. But increasingly rare. Not because the books have changed, but because the space around them has. The conditions under which we read now—the design of the screens, the rhythm of the scroll, the hum of elsewhere—aren’t made for it. They tug us toward movement, skimming, task-completion. They reward speed, not surrender.

And yet reading was never really about efficiency. It was about entering another mind and being changed by it. About letting a sentence unfold at the pace of your own thoughts—or slower. About imagining something that’s not on the page, precisely because the page left space for it.

In What We See When We Read, Peter Mendelsund calls attention to the way words conjure images that are never quite clear, never wholly resolved. Fiction works not because it tells us what things look like, but because it lets us begin to see. The image comes from the reader’s own half-conscious assembling, a blur of memory, suggestion, desire. Visual imagination, Mendelsund reminds us, thrives in what is left unsaid.

We don’t need to go back to parchment and candlelight. But we might remember that books once invited margin scribbles, layered glosses, silent conversations between reader and text. Alberto Manguel writes of reading aloud to Borges and being surprised by his responses, how different their sense of a story could be even as they inhabited the same paragraph. That kind of difference is part of what makes reading human.

We’ve built interfaces that can hold everything, every book, every edition, every comment, every definition. But we’ve only just begun to ask how they might feel. What’s the emotional architecture of a reading environment? What’s the cognitive tempo? What does it mean to design a space where the mind is permitted to wander—slowly, attentively, even playfully?

John Berger reminded us that seeing is never neutral. Every image carries a perspective, an ideology. Reading is no different. The layout, the margins, the typography—all of it shapes how we receive the text.

Sven Birkerts speaks of “vertical reading”—not the skimming of surfaces, but the sinking into time. The kind of reading where you forget what hour it is. Where a line glows, then fades, then returns to you days later. What scaffolding might support that kind of attention in a digital space? Maybe it’s a screen that darkens everything but the paragraph you’re in. Maybe it’s a command to pause.

There’s no one form this will take. No single app or platform that will solve it. But there is, perhaps, a mood we can design toward. Less extractive, more porous.

And there’s something else. Reading, at its best, doesn’t just reveal characters or arguments. It reveals us to ourselves. Lisa Zunshine and Keith Oatley have both suggested that fiction trains our capacity for empathy, for perspective-taking. We read to inhabit other minds, but also to practice recognizing our own. To see how we think. To notice what moves us.

Could an interface learn to notice that too? Not in a data-mining, ad-targeting way. But gently, responsively. “You lingered here—was there something in this line?” Or: “This metaphor reminded you of something. Want to trace it further?” Prompts to notice your own noticing.

Reading has always been a strange kind of solitude. It’s where we meet others across time and also meet ourselves. If we are designing for the future of reading, we are also designing for the future of introspection, attention, and imagination.

There’s a line in Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler that begins: “You are about to begin reading Italo Calvino’s new novel...” And from there, the book begins folding in on itself—reader reading about reader, story inside story. It’s a reminder that every reading experience is recursive. The book is reading you, too.

Not every tool needs to do this. But some should. Because the book, as we’ve inherited it, is already a kind of miracle. And the book we haven’t yet designed might be even more so.

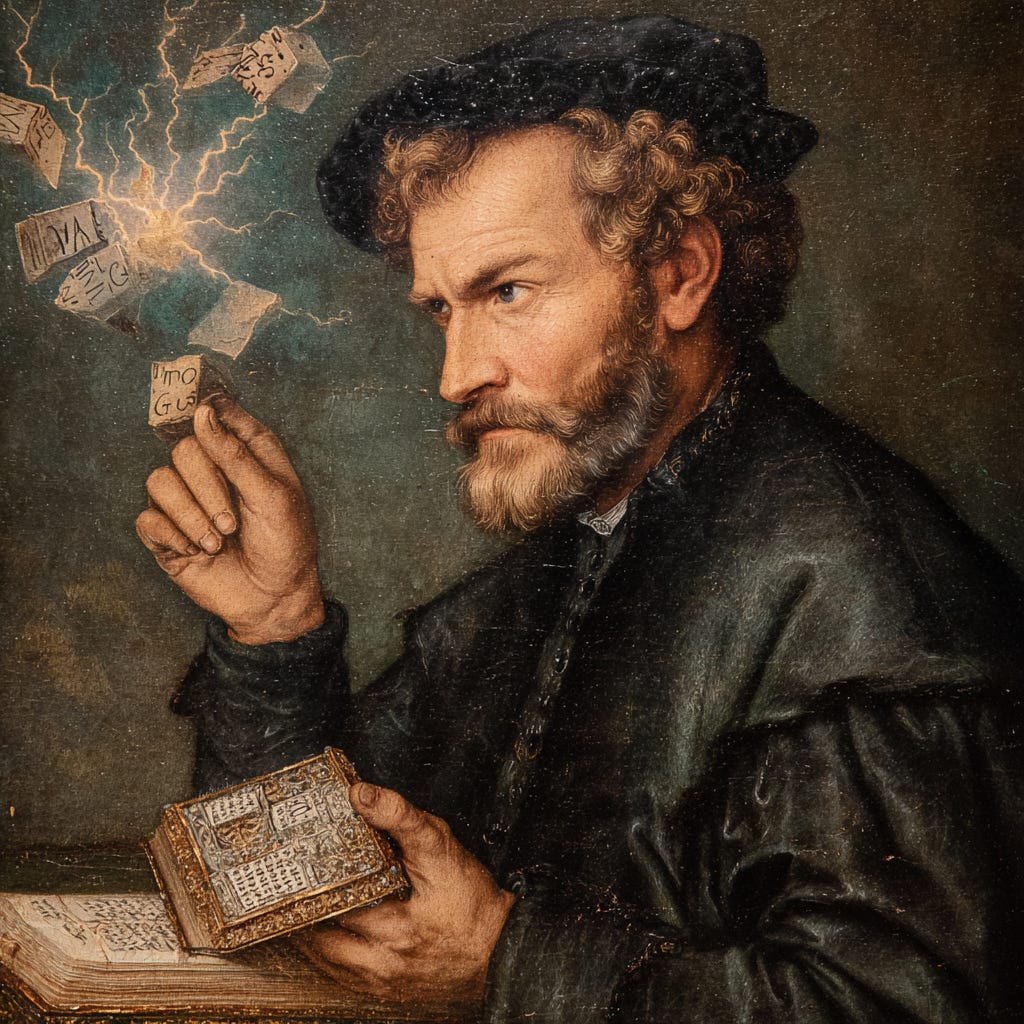

Jewish tradition imagines God studying Torah and creating the world by peering into the letters, but we never stop to ask what God’s Torah looked like. What was its interface. In creating the coming book, perhaps we approximate the divine one.