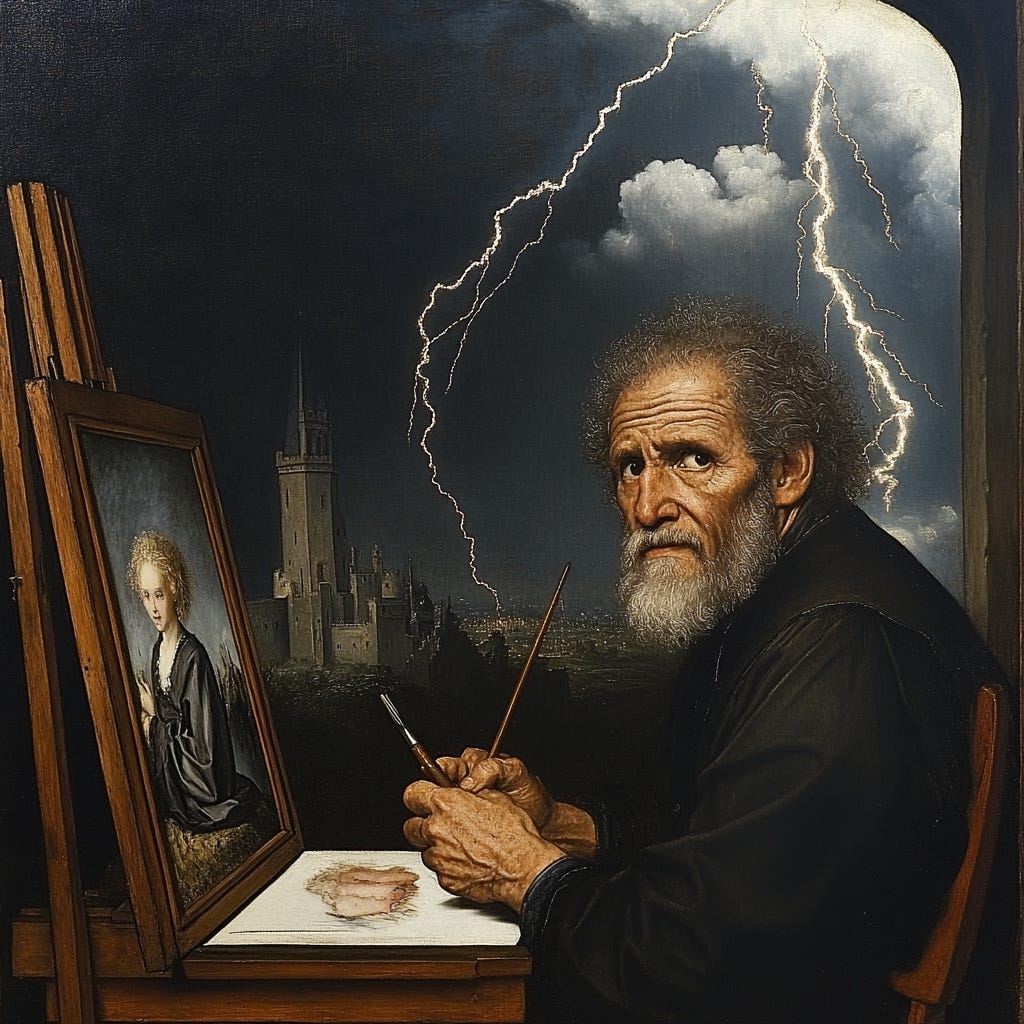

Once, to be seen was to be painted. Portraiture in the Renaissance was a public consecration of private power, a lavish assertion of one’s singularity in the face of death, anonymity, and time. The brush transmitted status. To sit for a portrait was to be rendered in the medium of immortality. Think of Hans Holbein’s painting of Thomas More: a visual philosophy of dignity, intellect, and influence, where every detail, the velvet robe, the gaze, signaled political and personal gravitas.

Then came photography.

With the camera, likeness became reproducible. Portraiture was democratized but also, paradoxically, cheapened.

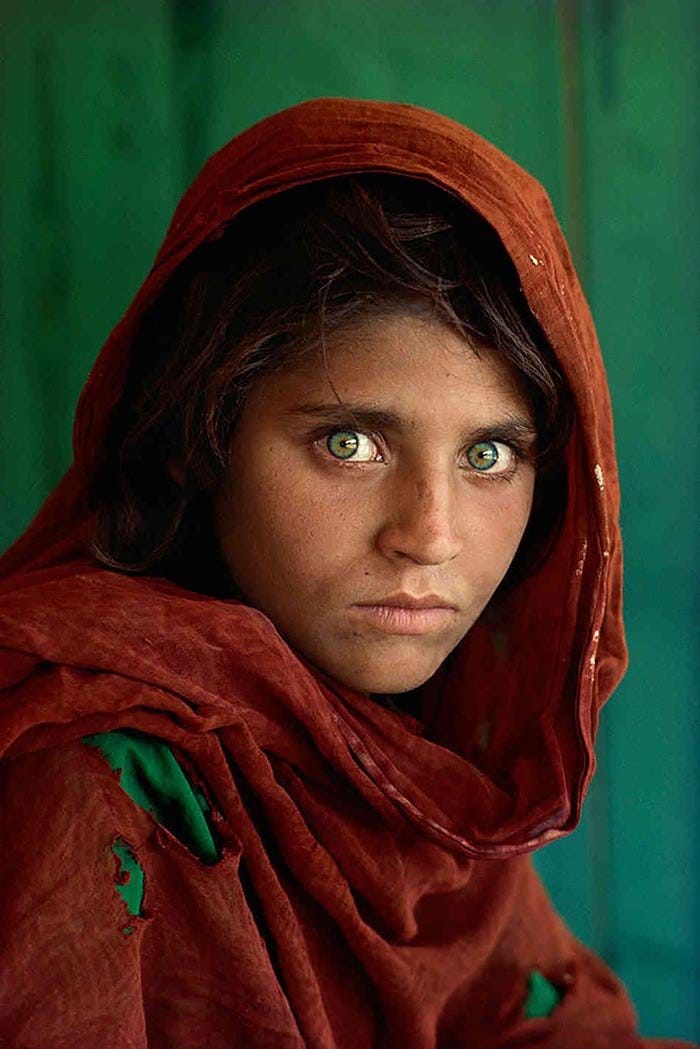

The distance between viewer and subject collapsed. No longer mediated by an artist’s hand, the subject now faced the clinical eye of the lens. As Susan Sontag observed, the photograph carries with it a trace of death: each shot a memento mori, a freeze-frame of time’s passage. Yet it also proliferated identity. Everyone could have a photo. Celebrity, once associated with noble or divine uniqueness, now hinged on visibility. Consider the carte de visite phenomenon in 19th-century France, calling cards with photographic portraits that circulated among the bourgeoisie, precursors to today’s Instagram grids.

And then came the iPhone.

The selfie completed the revolution that photography began.

The act of portraiture was no longer mediated by painter or even by photographer. The subject became the artist, the curator, the publicist. Instagram collapsed the distance between portrait and billboard: to be online is to be on display. Where portraiture once conferred status by rarity, the selfie demands attention by volume. What was once a luxury, the representation of the self, has become routine, even addictive. The aura is gone, to borrow Walter Benjamin’s term. The portrait and the self-portrait have been industrialized.

But something curious is happening.

In an era of infinite replication, luxury returns through limitation. The future of portraiture, I want to suggest, is not the infinite scroll but the bespoke AI avatar. Not the mass selfie, but the personal AI.

Imagine this: an LLM trained not just on language but on your select corpus.

Your writings, your emails, your tone, your syntax. Your voice. A digital portrait not of your appearance alone, but of your thought, your style, your personality. If the Renaissance portrait sought to capture inner dignity through outer form, the AI avatar might reverse the direction: revealing the form of the soul through its language.

Custom GPTs already exist. Anyone can spin up a chatbot in their image. But the difference between mass-produced avatars and bespoke ones may become the next frontier of cultural capital.

In a world where everyone can generate a selfie-bot, the elite will seek avatars that are curated, trained, and fine-tuned with the care of an oil painting.

Think of it as the Medici commissioning not just a canvas, but a sentient reflection. Already, some technologists are paying engineers and writers to create posthumous simulacra of parents or mentors, “grief tech” that feels more like a living archive than a static memory.

Here, media theory offers clues. Marshall McLuhan noted that every new medium reverses into its opposite when pushed to its limit. The selfie, pushed to ubiquity, becomes meaningless. But the AI avatar, a simulation of self in dialogue, reverses that trajectory. It offers a new scarcity: quality of likeness. Not how often you post, but how deeply your avatar knows you.

Portraiture once flirted with idolatry: making images of the human in the likeness of the divine. The AI avatar presents a secularized reprise of that ambition: not to worship the self, but to offload it. To externalize and preserve one’s voice in a tool, a companion, a memory-machine. In a society obsessed with productivity, the self becomes a bottleneck. The avatar offers continuity. Delegation. Even immortality.

It also offers something unique, a representation not in visual form, but in auditory form.

And so, just as the wealthy of Florence once vied for the finest painter, tomorrow’s elite may seek the finest AI artisan, someone who knows not just the technical requirements of LLM fine-tuning, and not just the taste requirements of app development, but the thinking requirements of a humanist and the pedagogic requirements of a teacher.

The truest likeness will be measured not in brushstrokes or megapixels, but in resonance, a profound and paradoxical concept. For what is a likeness? Here, a purely technical person will not be able to help. As Heidegger writes, “Science doesn’t think.” While the academic world rejects and fears tech and the tech world conflates building vertical SaaS products with thinking, a new opportunity for the philosopher-builder.

The arc of portraiture bends, then, from pigment to prompt. From depiction to dialogue. And in that turn, we may rediscover not only the value of being seen, but the deeper desire to be understood.

P.S.—If you’re a rich thinker with a great body of work, seeking to create an artisanal AI avatar, Lightning can help. Get in touch: hello@lightninginspiration.com

Cheers,

Zohar

Beyond dialogue, it would be wonderful if the avatar could also visually represent the internal complexity of the avatar’s subject, the way Rembrandt’s portraits so profoundly do.